Diving for Hidden Treasure: Mussel Surveys in the Mississippi River

By Alora K. Jones

2017

Did you know the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area has a scuba team?

Yes, you read that right. As part of the Mussel Coordination Team (MCT), Ranger Allie Holdhusen has been holding it down for us at MISS when it comes to studying and monitoring our freshwater mussel populations. The MCT is an interagency team comprised of several state and federal agencies, academia, private consultants, private citizens and others who are all working together on conservation of freshwater mussels.

These faceless, rock-like creatures live in the bottoms of rivers, streams, and lakes, performing a crucially important job: filtering our water to remove harmful bacteria and other pathogens that would otherwise contaminate our primary source of drinking water. So while they may not be quite as lovable as the majestic bald eagle or playful river otter, these hidden figures certainly deserve our love and appreciation.

The Mississippi National River and Recreation Area is home to nearly 30 native species of freshwater mussel, many of which are on the state and federal endangered lists. Changes in habitat, threats to water quality, and competition from invasive species like zebra mussels are all factors that threaten our mussel populations, which is why Allie and other partners are keeping a close eye on them in our park. She gave me the rundown on this project before I joined on the survey to provide assistance.

“Three years ago they found some 600 winged mapleleaf mussels, which are endangered, and now only naturally occur in the St. Croix River. They split those 600 babies into several reintroduction sites, two of which are right here in Saint Paul. Last year we reintroduced 170 individuals at two different sites, and this year we’re going back to those aggregation sites to see if any of them are still in there and measure their growth.”

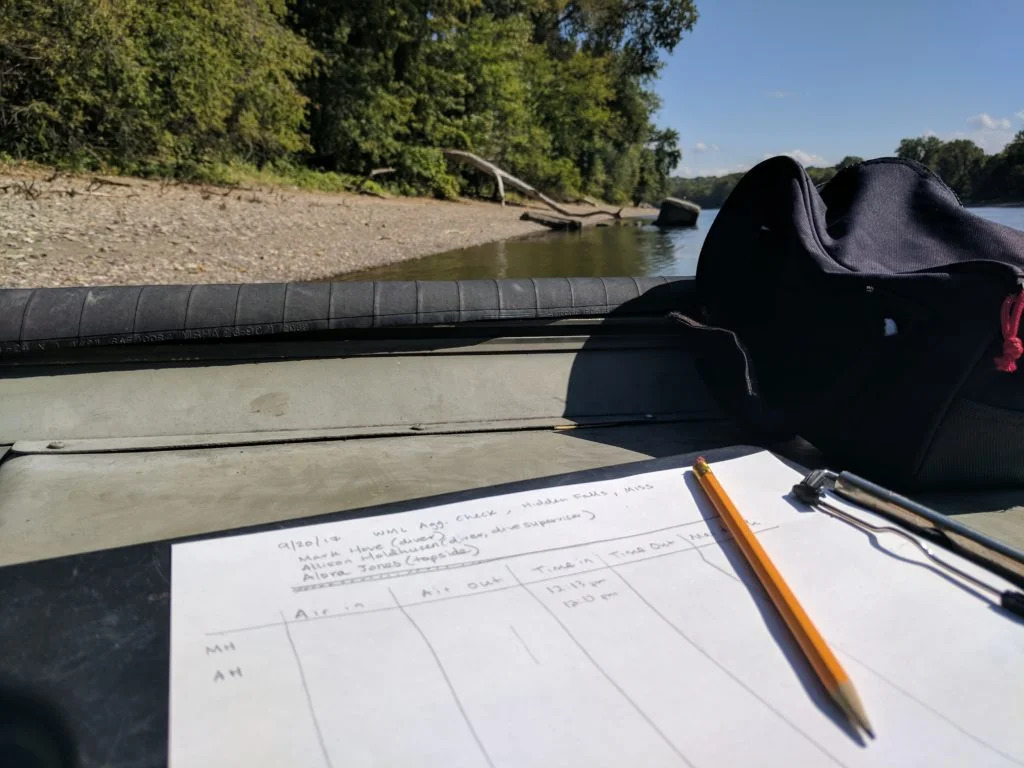

I was fortunate enough to accompany Ranger Allie on a mussel survey recently, along with Mark Hove, a researcher with the University of Minnesota and Macalester College. Along the way I learned a lot about the project, our local freshwater mussel populations, the threats they face in the reintroduction process, and even more about scuba terms. As they were gearing up in their wetsuits, weighted belts, and rock boots, Allie and Mark walked me through some of their hand signals and how to respond in the event of an emergency.

Mark has been doing this work for a while now, and over the years has collected lots of interesting stories from these excursions. “Once at Hidden Falls, across from the dog park, a woman started hurling rocks into the river at our dive flag, saying ‘You shouldn’t be here!’ Who would’ve guessed something like that would have happened?”

Incidents like this highlight the importance of having another person above the surface, known as the topside, to keep an eye out for oncoming boat traffic and occasionally people throwing rocks. Normally this role is filled by a volunteer, but if one isn’t available then staff members get to step in as topside, and sometimes even help with data recording. In truth, the bulk of the work involved sitting on the beach sunning myself, and occasionally waving off boaters who came too close to the divers — a tough job indeed!

Once back at the surface, Mark and Allie waded back to shore holding their bag of hidden treasures! After taking some time to warm up (turns out diving makes you extremely cold) they got to work identifying and measuring the growth of these mussels, while I recorded and read back the data to them.

Over lunch, Allie and Mark explained the next part of their diving day: to place monitoring cameras in a river bed in order to try and capture the reproduction process of the winged mapleleaf mussels, which for a time involves a parasitic relationship exclusively with channel and blue catfish. More on that process here.

While few of us see or hear much about the freshwater mussels of our mighty river, there are many people within the National Park Service and beyond that are dedicating their time and energy to studying and protecting these crucially important animals. For all the benefits that freshwater mussels provide, and all that they can tell us about the health of the Mississippi River, we should all be paying closer attention to what lies beneath the surface of our national park.